The following book review essay of Imagining the Heartland: White Supremacy and the American Midwest, by Britt E. Halvorson and Joshua O. Reno will appear in an upcoming edition of one of my favorite academic journals, the Middle West Review: An Interdisciplinary Journal about the American Midwest. It will likely appear there in a shortened version, and the editor, Jon K. Lauck says it’s fine with him if I publish this longer version here. Being an academic journal, they will also likely clear up a few of my word choices. And long rambling sentences.

Regardless, this is one of the most frustrating books I have ever read, and this is the first negative book review I have ever written. It would have been easy to set it aside and not do it, but the deeper I got into it the more I realized that the book, and more importantly, the social sciences in general, needed to be reckoned with. So here goes.

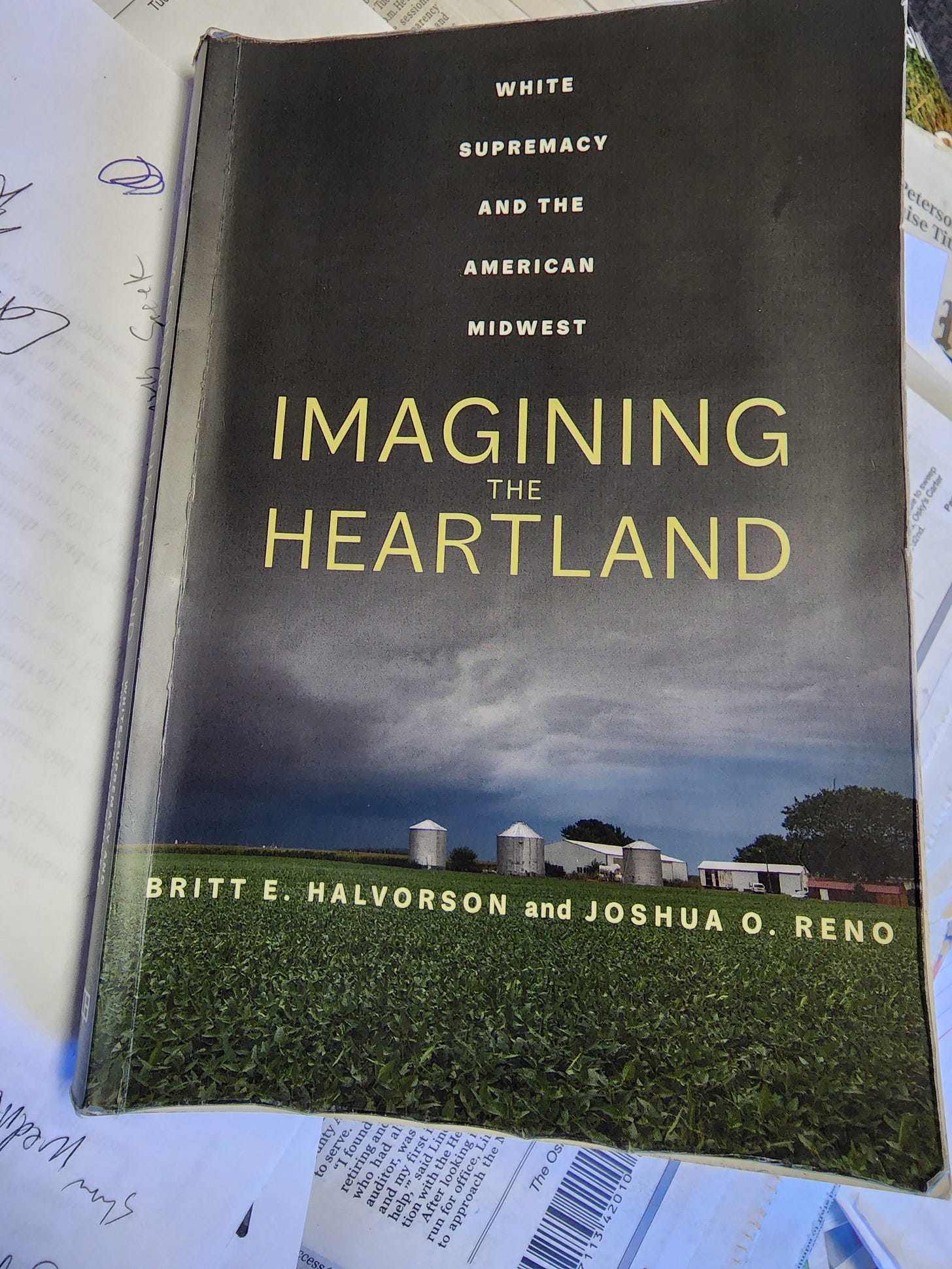

This past summer, I went to my post office box in Bussey, Iowa (population 379), and was delighted to see I had a book in the mail. I ripped the package open and saw the title was “Imagining the Heartland: White Supremacy and the American Midwest.” Interesting, I thought. Yep, White Supremacy is in the Midwest. O.K. I’ve seen it, and some of its effects. I imagined a thoughtful discussion of the KKK, maybe how systematic racism is playing out in state legislatures, or even more interesting, a discussion of contemporary midwestern white nationalist “Christian” church groups, or racist right-wing militia gangs.

I turned the book over, and read the “blurb” by Joseph Darda--”The heartland isn’t a region. It’s a race. Britt Halvorson and Joshua Reno have written an absorbing book about how images of boring white folks secure white dominance.”

I was stunned. What hubris, I thought. The arrogance, the condescension…

Not quite. What I actually thought was “what bullshit.” While I very much doubt this was Darda’s intention, in three sentences he not only mischaracterized all of the peoples of the region, he wiped all minorities off of the map.

This book pissed me off before I had even left the post office, and it didn’t get much better as I slogged through it, considering their “logic” and “evidence.”

The authors are going to say I’m missing their point. That I don’t understand them. They are surely correct--in part.

But before we can figure out if I am missing their point, we have to figure out what their point is--and it's not clear. Surely it’s more than what Darda wrote?

OK, here is their point, as near as I can figure. The book begins with a reference to a conversation talk show host Dick Cavett had with movie director Orson Wells in 1970. The authors say “Cavett was incredulous that such a global and cosmopolitan figure (Wells)…was from such an underwhelming place…” That underwhelming place was Kenosha, Wisconsin.

The authors continue in reference to the Cavett-Wells conversation:

“In this book we take issue with this underwhelming quality, this banality, and asked a series of questions that emerge from it: what are the conditions that make regions appear average, plain and homogeneous, and what are the social, political, and cultural consequences of this? Our central argument is that if one can understand the ways in which a region and its people do not seem to matter, then national and imperial projects of race and inequality can be understood and challenged in a new way…we argue that the Midwest--as an imagined national middle, or average, is less a real place or collection of places and more a screen onto which various conceptions of middle-ness and average-ness are projected. Put differently, the Midwest serves as a standard and has for many years, one that allows for normative claims about the state of the nation and fosters projects of structural violence from white supremacy to imperialism and nativism.”

We are “average, plain, and homogenous,” “banal,” “don’t seem to matter,” “middle-ness and average-ness” are projected on us, resulting in “normative claims,” and “fosters projects of structural violence?”

Right…

If this is their point, I “think” I understand it, and after consideration of their logic and “evidence,” I reject it for reasons I’ll give below. I also may have missed at least part of their point because they wrote this book without much effort to make it possible to understand it.

This cloud of academic ambiguity throughout much of this book is frustrating, and yet all too common in the social sciences. Like a mediocre poem in The New Yorker, we are left to intuit its meaning, much like a shaman reads goat entrails as he or she seeks to interpret the world around them. Yet, we assume the poem must be profound since it’s in The New Yorker, just as Halvorson and Reno’s book must be profound because it’s published by the prestigious University of California Press by professors. Because of their shared ambiguity, what the hypothetical poem and the book really share is way too much pompous smart people gibberish.

Starting with the author’s “central argument (which is actually a central assertion)” at the front of the book, we eventually get to Darda’s “blurb” that “images of boring white folks secure white dominance,” at the back of the book. The authors assert boring white folks secure white dominance innumerable times, in one way or another, throughout. It’s like they think if they say it enough times, maybe the reader will believe it (this is so Trumpian--”the election was stolen,” “the election was stolen,” the election was stolen,” and “I declassified the documents in my mind!”)

Darda, in the role of Shaman, is apparently better at reading goat entrails than I am.

The choice to start with the Cavett interview of Wells is interesting, but not in the way the authors see it. As they note, Wells was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin. What they don’t say is Cavett was born in Buffalo County, Nebraska. Two major figures in the American entertainment industry at the time, with midwestern birthplaces, are allowed to joke about the region of their birth. Which is likely why Wells didn’t take offense. Cavett and Wells both knew their conversation was a subtle piece of resistance to/rejection of, the flyover narrative about the midwest that coastal elites have shaped for decades.

That’s how I read the goat entrails, anyway.

It’s here where the authors first problematically conflate people and place, which they do throughout the book, adding to the book's general opacity, but Cavett’s interview of Wells not only doesn’t fit their narrative of banality, it refutes it.

There is another way the authors might think I’m missing their point--intellectually. Perhaps.

While I recognize the importance of Critical Race Theory in examinations of society, I’m not a critical race theorist, but I shouldn’t have to be to understand what they are trying to say. This problem goes well beyond this book and permeates all of the social sciences. It’s almost as if the vast majority of authors in dozens of fields of study are allergic to clarity. Conciseness too, while I’m at it.

Where clarity in writing is obtainable, but where writers choose not to be clear, several reasons come to mind. The first is laziness, but Halvorson and Reno don’t seem lazy, as they both have Ph.D.s and tenure, and have put considerable work into this book. Why put all of that work into the book, and not be clear about what they are trying to say? And why is it so common in the social sciences in general? Just like in much of the social sciences, this book oozes gobbledygook.

The second reason to be opaque in writing is that it’s the gateway to ambiguity. As the great midwestern comedian Emo Phillips put it, “ambiguity is the Devil’s volleyball.” Social scientists are often ambiguous when they haven’t thought something through, recognize their own convoluted or inconsistent logic, but don’t want to admit it, or want to believe in their thesis so much they choose to gloss over any problems that someone might recognize, so they hide behind ambiguity.

The third reason to be ambiguous is that it is part of an accepted, and even demanded, performative art in academia. With ambiguity comes power. With many academic readers, if we don’t understand something, we automatically think maybe we should just work harder at understanding it, and if I’m having to work hard to understand Author X, Author X must be smarter and/or more informed than I.

And the general public? They have absolutely no chance of understanding it in the rare possibility they encounter it. Zero, zilch, nada, even if they had enough time and interest to tackle it. And what’s the result of this? Resentment. Public resentment that is currently being used by the far right to attack the academy from coast to coast. Blame the far right all you want, but the core of the problem is within the academy itself for not producing products--when we can--that are accessible, of interest, and valuable to the public.

Now that I’m on a rant, I want to tie it up in a bow. The real problem is the traditional structure of the tenure system. Research, teaching, and service to the institutional community are at its core. Rarely is public outreach rewarded. In fact, too much of it can hurt your career, in that department chairs or deans might tell a young faculty member so inclined that they need to focus on what “matters.” Sometimes there is even disdain in the academy for those who popularize their work or their discipline. I’m old enough to remember when academics used to say, “well, I hear Carl Sagan wasn’t such a great astronomer, anyway.”

Part of the reason I may not understand some of what the authors are trying to do is also that they are part of a social science culture that really doesn’t care who understands it, if anyone. Understanding is irrelevant. The prestigious publication and the few lines on the vita are the feather in their cap and all that matters. For many, it’s all performance; for their administrations, their peers, and their students. That and for a dozen or so grad school buddies who will pretend they actually read the work. Realistically, some may really seek a broader audience, but they don’t know how to achieve it, and receive no institutional or peer support when they try.

As noted above, I’m honest enough to admit I may not understand or appreciate some aspects of this work. Point taken. I’d say, educate me, but the authors missed their chance. Regardless, I don’t think the authors are smarter or more informed than I am in general. I think that they are trapped in an intellectual academic cage hundreds of years in the making that is now under assault. It’s not in an “ivory tower.” It’s in a dark, stuffy, cave.

Performative academic ambiguity and disdain for a public audience have long been common in the academy, and used as a lever of social inequality, both in and out of the academy, and it’s now biting us on the ass. And anyone reading this, myself included, is likely part of the problem.

It doesn’t have to be this way. My first lessons in anthropology were long ago, and began when I was younger than ten years old. My first instructor was the great anthropologist Margaret Mead. I eagerly awaited her lesson that arrived every month in her column in my Mom’s Redbook magazine.

But back to the review, and more problems with the book.

The authors don’t clearly differentiate between real white supremacists, e.g., historic KKK members and Oath Keepers, from the white Walmart greeter, the white coffee shop waitress, or the white road crew worker. They just don’t use Maslow’s hammer to bludgeon the midwest, they use Maslow’s sledgehammer, and hit everything that moves with it. I don’t think the authors mean to call everyone in the midwest a white supremacist, but they inadvertently do so with ambiguity and by conflating people and place.

While the authors cite and seem to embrace Tamara Winfrey-Harris’s admonition to “Stop Pretending Black Midwesterners Don’t Exist,” this is exactly what they do, with only token mention of the important roles minorities play here now and historically.

Their research didn’t start with a question. It started with a conclusion. While the authors are never this clear, I’d like to summarize what I believe that conclusion to be--that familiar midwestern tropes reinforce, reflect, and maintain white supremacy and power like no other region does. If the authors disagree, too bad. They had a chance to be clear and chose not to.

They then cherry-picked “evidence” that supported that conclusion. Some of that evidence was interesting and convincing, e.g., how Henry Ford and the Nazis exploited midwestern peoples and tropes for evil ends. I just saw another example in an ad Florida Governor Ron DeSantis released in November of 2022--a riff on Paul Harvey’s famous "So God Made a Farmer" speech to the Future Farmers of America in Kansas City, Mo., in 1978. The late Harvey's voiceover became a Super Bowl ad for Ram Trucks in 2013. In the DeSantis ad, “God Made a Fighter,” which of course is DeSantis. It’s pure idolatry, and every Christian should be offended, but white “Christian” Nationalists will gobble it up.

Other examples the authors pull from art, literature, and film fall flat, e.g., the works of Willa Cather, Grant Wood, and the movie the Wizard of Oz. And here I thought my latest book, Deep Midwest, was a loving tribute to family, place, and people. Little did I know that the slim volume of short stories and poetry was helping reinforce, reflect and maintain white supremacy.

But let’s say, however, that every example used in the book shows how the midwest was used in exactly the way they say. Let’s assume every single example works.

The fatal flaw is that this frame could be imposed on any region, and the conclusion will also hold for that region. For example, let’s take the “west” and “western” and substitute them for “midwest” and “midwestern” in the conclusion referenced above that “common western tropes reinforce, reflect and maintain white supremacy and power like no other region does.” Then pile on the evidence, substituting, say, Zane Grey for Willa Cather, Frederick Remington for Grant Wood, and the John Ford movie “The Searchers” for “The Wizard of Oz.”

Boring white people are everywhere in rural “uninteresting” places in America, and if we wanted to, we could make a similar argument for any of those regions.

I hauled this damn book around all summer and part of the fall, trying to make sense of it whenever I could find a few minutes to read. My copy is worn, dog-eared, with folded page corners, marginal stars and exclamation marks, underlined phrases, and illegible marginal notes. It has traveled thousands of miles with me.

A friend saw it and asked me what I was reading. I handed it to her, not saying a word. She’s a Black communications professor who grew up in Iowa and the South. She’s a former UN spokesperson who worked in Somalia. She looked at the cover, thumbed the pages for a moment, then turned to the back cover. “The Midwest?” she asked, “But what about the South?”

Indeed. What about the South?

I want to take issue with the author’s use of the midwest and its white residents as “banal.” They love that word as they describe us. They use it so often that I’d like to look at their keyboards to see if the surfaces of the B-A-N-A-L keys are worn down. All-knowing Google defines “banal” as “so lacking in originality as to be obvious and boring.”

Don’t they realize that this is insulting? Call someone “banal” at any of the local watering holes where I choose to self-medicate and you just might get poked in the nose. I seriously thought about going to a local bar on a Friday night after work, standing on a chair, and doing a reading from a random page of the book to the crowd. People would roll their eyes, laugh, and then playfully boo me until I stepped down. Someone would buy me another beer.

These people aren’t banal, no matter how many times the authors repeat it. My people aren’t banal.

Ambiguity aside, it’s language like this that further isolates the academy from other people. Most of us went to public schools. Most of us went to public colleges or universities. And even if we didn’t, we drive on public roads and use public services. Don’t you think we could at least respect the public? Try to use our privileged positions to help make their world better?

There is one more thing I want to get at in this book, and in the larger academic community that I find troubling. The performative, self-serving, self-reflections that are all too common. In their “reflections,” especially the final one, the authors almost wallow in despair about their whiteness, wringing their hands, bemoaning their privileged lives and upbringings, until they fully achieve victim status because of their whiteness and privilege!

If this were real life, I would be tempted to walk up to them and hold them as they sobbed on my shoulder, whimpering, while I patted their backs, whispering in their ear, “it’s going to be OK, it’s going to be OK, it’s going to be OK, until they feel better.

But they would probably charge me with assault.

Seriously, it’s reflections like these, and ambiguous and broadly cast allegations of White Supremacy that are grist for the propaganda mills of the Steve Bannons and Christopher Rufos of the world.

That’s all, except for one more thing. No, two more things. First, while my review was ostensibly of Halvorson and Reno’s book, my main criticism is of the academy, especially in the social sciences where they were trained. The far right is coming for you, and you better be ready to fight for your discipline and academic freedom. The immediate fight will be political, but long-term victory will only come from engaging with the public honestly and purposefully, sharing results of research or artistic efforts that make their lives better in an understandable way.

Finally, if I’m going to toss out Halvorson and Reno’s work, I feel the obligation to leave readers with a different story--not of a White Supremacist midwest, but of an overall historically progressive midwest that led the nation in advancing opportunity and equality. Yes, we have made mistakes, and there are terrible stories to be told in any history. Ultimately, we need to acknowledge and learn from our mistakes--and teach them--and celebrate our common victories. My focus is on Iowa, since that’s all I really know, but I suspect other readers here can tell similar stories about the midwestern states where they live.

The midwest, Iowa in particular, isn’t a reflection of white privilege like the authors assert. Here I repeat Darda’s statement to make it fresh in your minds.

Joseph Darda--”The heartland isn’t a region. It’s a race. Britt Halvorson and Joshua Reno have written an absorbing book about how images of boring white folks secure white dominance.”

This isn’t true. Images can be used for good or ill, but the midwest isn’t a race. And my following argument is clear, and unambiguous. Normally I would rework the following passages, but this book has already taken too much of my time, and my deadline is now. So forgive me, some of the following paragraphs have been plagiarized from my “How Democrats Should Talk to People in Farm Country; Like Barack Obama, Deidre DeJear, an African-American small-business owner and candidate for Iowa secretary of state, stresses opportunity, voting rights, and unity,” published in the New York Times on September 20, 2018:

Iowa has a progressive record on race that may be unsurpassed by any state in the country. In 1839, the Supreme Court of the Iowa Territory, in its first decision, ruled that a slave who had reached Iowa soil was free and could not be forced to return to a slave state.

Iowa legalized interracial marriage in 1851, a century before most of the rest of America. The 22nd Iowa Volunteer Infantry Regiment helped break the back of the Confederacy as part of General Ulysses Grant’s siege of Vicksburg.

African-American men were granted the right to vote in 1868, two years before the 15th Amendment to the Constitution.

On Sept. 10, 1867, 12-year-old Susan Clark, a Black girl, walked uphill from her home in the center of Muscatine to Grammar School No. 2, a whites-only school, with the encouragement of her father, Alexander Clark. She was denied entrance because she was Black. Alexander Clark sued, and as a result, Iowa outlawed segregated schools in 1868, a century before much of the rest of America. Yes, a CENTURY.

In 1884, the Iowa Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination in public accommodation.

On July 7, 1948, a 39-year-old Black woman named Edna Griffin entered Katz Drug Store in downtown Des Moines with her infant daughter and two friends. Griffin and her friend John Bibbs sat down at the lunch counter but were denied service by the waitress on an order of ice cream sundaes.

Protests and a boycott of the store by both black and white citizens ensued, and a lawsuit was filed. In December 1949, the Iowa Supreme Court ruled that Katz Drug Store had discriminated against Griffin and Bibbs. This boycott occurred seven years before the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, led by Rosa Parks. The Katz Drug Store folded.

Griffin is often called the Rosa Parks of Iowa. Another way of looking at it is that Parks should be called the Edna Griffin of Alabama.

These stories don’t appear in “Imagining the Heartland: White Supremacy and the American Midwest. Neither do similar stories. They are ignored because the authors want to make a different point. An erroneous, unfortunate, and patronizing one.

Iowa’s history--to date--is largely progressive. In these troubled times, we’ll see what the future holds.

Susan Clark, Alexander Clark, and Edna Griffin are heroes. Notice that they are the protagonists in these efforts, as were other Black Iowans in other milestones mentioned above. “Iowa” didn’t make it happen. White people didn’t make it happen. Because of their vision and leadership, Clark, Clark, and Griffin gained trusted allies who helped them make it happen, well before the rest of America. They deserve statues on our public squares to remind us not only how far we have come, but of how far we have yet to go.

And let’s not forget, without the support of Iowans, Barack Obama may have never been president.

If Halvorson and Reno and other similarly trained social scientists conclude that my narrative here is perpetuating one of their supposed white supremacist tropes, then God help us.

Given the subject matter of this essay, I would like to refer readers to my friend Joshua Dolezal’s Substack “The Recovering Academic.” Josh was a professor in the English Department at Central College in Pella when we became friends. He and his family relocated to Pennsylvania a couple of years ago to be closer to his wife’s family. Josh tackles the academy head-on with insightful and hard-hitting commentary. If you are interested in education in general and higher education in particular, The Recovering Academic is a must read. Plus, he is one of the best writers I know.

Here are the members of the Iowa Writers Collaborative, in alphabetical order. Please check them out and consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. To receive an invitation to the monthly “Office Lounge” Zoom meetings, you need to be a paying subscriber to at least one of our newsletters. Our November meeting is this upcoming Friday at noon, and the Zoom link will be sent to all paid subscribers. Please also consider supporting the great news source the Iowa Capital Dispatch which shares some of our work. Thanks for subscribing!

Too much to say about this to fit into a comment, but I love the points about performative ambiguity and the metaphor of the dank cave, rather than the ivory tower. As I'll write for Tuesday's newsletter, a lot of this ironically mimics American Puritanism. Maybe a sliver of John Winthrop's audience could have understood his logical method and argument in "A Model of Christian Charity," but flourishes from the pulpit were common strategies for lording authority over the common people and keeping them in their place. The American university was born of the Enlightenment and the Early Republic and could use a dose of the clarity and rationality that one finds in, say, Benjamin Franklin.

As a fellow social scientist, rural sociology MS from Iowa State, I couldn't agree more with Dr. Bob. I got a degree in rural sociology because I wanted to change the world. It's served me well. But often I feel like the outlier rather than the norm. It seems the two big groups in sociology are academics and marketers. Learning how to think, write, and act through a scientific approach has supercharged my ability to engage and help advance social change. I encourage any younger person who wants to be a change maker, which is almost all of them that I've met, to study whatever field they are most interested in and then figure out how to use what they've learned to build a life of learning and action. Bob calls out the bullshit that actually undermines the entire movement of liberal education. And the consequences of that bullshit go far beyond making stupid generalizations about my people, mid-westerners.